"The World:Reglitterized" in München Kunst als Kettenreaktion

"The World:Reglitterized" in München Kunst als Kettenreaktion

July 30, 2021 by Victor Sattler

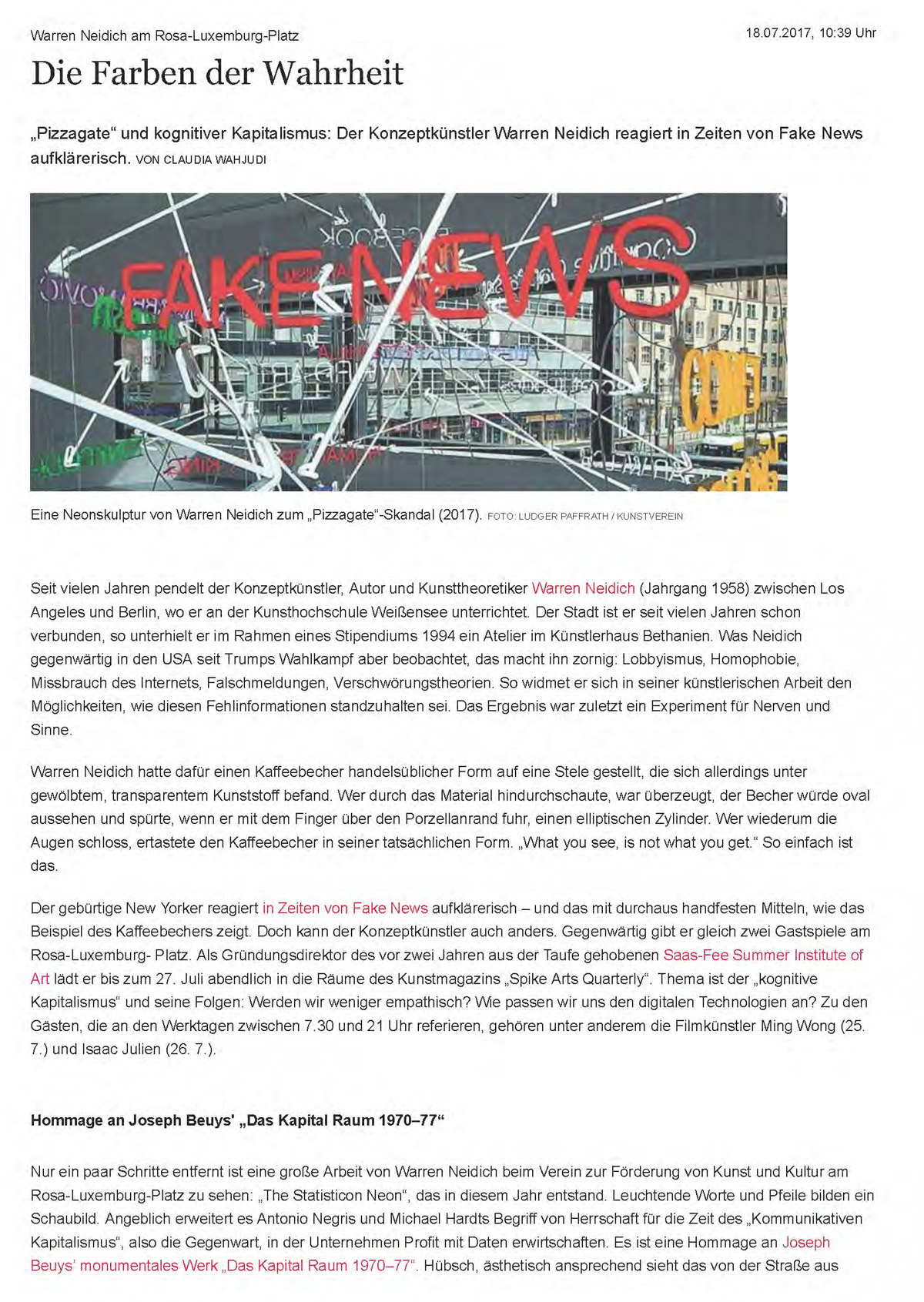

“Warum die Folgenlosigkeit eine Utopie bleiben muss, zeigt Warren Neidich. In seiner bunten Neonlicht-Skulptur “Pizzagate”, die seit 2017 nur relevanter geworden ist, sind alle Wörter über gehängte Folgepfeile miteinander verbunden. Die moderne Netzwerkgesellschaft wird als Wortfeld, Edelstein oder Nervensystem dargestellt, und niemand kann sich ihrer ganz entziehen: Weil die Performancekünstlerin Marina Abramović im Jahr 2016 zum festen Inventar einer rechten Verschwörungstheorie aus den USA wurde, steht bei Neidich sogar ihr Name in Verbindung zu “Satanismus”, “Menschenhandel” und “Pädophilie”. Für diese Verleumdung reichte es aus, sich mit Kunstsammlern aus dem Dunstkreis von Hillary Clinton sehen zu lassen. Den Rest erledigte das Internet, die Kettenreaktion nahm ihren Lauf.” – Victor Sattler

Interview with Warren Neidich About Wet Conceptualism

Interview with Warren Neidich About Wet Conceptualism

November 19, 2023 interview by Gary Ryan

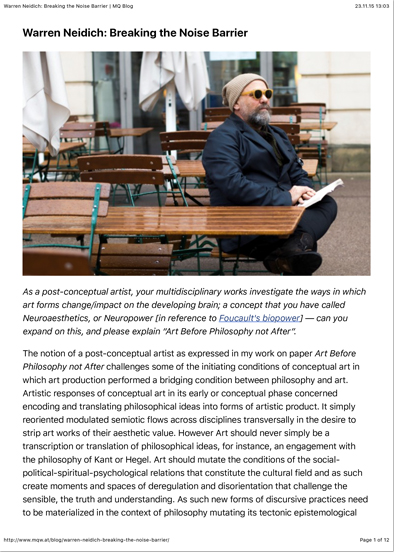

“In 1999, Neidich curated the exhibition Conceptual Art as a Neurobiological Praxis, at the Thread Waxing Space in New York City. Then as now, many of the works in the show did not fit within the scheme originally described in the mid-1960s as conceptual art with its non-representational, text-based character, anti-formalist, unemotional aesthetics, and reliance on immateriality. Wet Conceptualism served as a response to his own frustrations concerning his own work which he always had felt was conceptual, but which was not appreciated as such. With the expansion of the age-old term, Neidich’s work, and many other deserving artists can be understood in a larger but more precise sense of the term.” — Gary Ryan

We don’t want to live in a Universe, We want to live in a Pluriverse!

We don’t want to live in a Universe, We want to live in a Pluriverse!

September 3, 2023 by Joseph Nechvatal

“But the star of the show is Warren Neidich’s neon speculative philosophical wall piece A Proposition for an Alt-Parthenon Marbles Recoded: The Phantom as Other # 2 (2023). It schematically proposes that the illusory sensations of imaginary phantom limbs might operate metaphorically as a means of empowerment to the future despotism of what the political philosopher Antoinette Rouvroy calls algorithmic governmentality or what Bonaventura de Sousa Santaos calls epistemicide.” – Joseph Nechvatal

ART / THEORY: Warren Neidich

ART / THEORY: Warren Neidich

Summer 2023 by Sanford Kwinter

“Neidich’s project of connecting our somatic, noetic, and nervous system machinery to our social and economic ones, as so many ways of arranging material and sensible worlds, has created a new framework. It is a framework developed across a dozen books, global conferences, an art practice, and a school. And more importantly still, Neidich assembled an international community of theorists, artists, scientists, and philosophers who continue to generate work as part of an expanding program to rethink human ecology and imagination in an increasingly imperiled world.” – Sanford Kwinter

Wet Conceptualism

“The notion of wet conceptualism is posited against mainstream conceptual work, in this context “dry:” what comes to mind in this context are works such as An Oak Tree (1973) of Michael Craig Martin, or the oeuvre of Joseph Kossuth. There are borderline cases presented in this novel and convincing survey of sweeter, more rosy conceptual art: ironically, co-curator (with Sozita Goudouna) Warren Neidich’s piece Art Before Philosophy After Art (2015) sits firmly on this middle ground. Text based, it demands reading, presenting a title-as-text-as-list. But the text dissolves in a murky green form, a modernist assemblage, the Braque-like form underlines Neidich’s point that wet involves seductive color and significant form, formalist signifiers, on top of an insistence on the didactic-as-form.” – William Corwin

Neuroactivism: This is how it will free our brains from the grip of big tech.

Neuroactivism

This is how it will free our brains from the grip of big tech.

October 14, 2022 by Anders Dunker

“Our physical brains have become ‘a locus of capitalistic adventurism and speculation,’ writes artist and theorist Warren Neidich, editor of a new anthology called An Activist Neuroaesthetics Reader (2022). Through his collaborative project ‘The Psychopathologies of Cognitive Capitalism 1–3’, Neidich has helped coalesce a burgeoning field of critical theory centred on the brain and neuroscientific theory. ‘The brain and new technologies have become a real battlefield,’ writes economist Yann Moulier Boutang – one of many veteran contributors from Neidich’s circle – in his contribution to the anthology.” – Anders Dunker

Interview with Warren Neidich – Artworks about Post-Truth Society and Activist Neuroaesthetics

Interview with Warren Neidich –

Artworks about Post-Truth Society and Activist Neuroaesthetics

October 5, 2022 by Hsiang-Yun Huang

“What connects activist neuroaesthetics to material philosophers is the idea that art is something of a record of a morphogenic ontology of aesthetic production, whereby the changing and historical relations – social, political, economic and historical – culminate in objects and things that express these changes. The form a becoming cultural milieu or habitus that then elicits changes in the brain. In fact, they mirror each other and coevolve together. The cultural matrix and the material brain are constantly evolving in tandem. The brain is not an unchangeable essence. The brain isn’t just in the skull. It is entangled with this extracranial component of the socio-political, economic and historical milieu. There is a morphogenetic process that is going on in this milieu, but there is also a morphogenetic process going on inside the brain. Bernard Stiegler called this a technological evolution rather than one instigated by genetic mutations alone, i.e. an exosomatic organogenesis.” — Warren Neidich

Warren Neidich: Museum of Neon Art

Warren Neidich: Museum of Neon Art

September 6, 2022 by John David O’Brien

“The elusive relationship of the brain and the mind has always fascinated without ever quite being resolvable. It is as though we collectively hold the convoluted gray mass that constitutes the brain in suspension with respect to its relationship to the entity whose non-physical indefinability is connected, although unclearly.”

— John David O’Brien

Warren Neidich: The Brain Without Organs: An Aporia of Care

Warren Neidich:

The Brain Without Organs: An Aporia of Care

September 2022 by Anuradha Vikram

“In a neurological sense, humans are already biological machines, in that our thoughts and actions are powered by electrical synapses. These countless tiny surges travel through the vast crenulated landscape of the brain, transported by axons that act as conduits to move energy from one place to another. For Warren Neidich, who studied neurobiology before becoming a conceptual artist, the workings of the brain are an endless source of fascination. His exhibition at the Museum of Neon Art, The Brain Without Organs: An Aporia of Care, takes a radically deconstructive approach to the brain as a material organ and as an emblem of human intellect, the source of our unique evolutionary advantage.” – Anuradha Vikram

The Hybrid Dialectics

“This interview between the writer and critic Erik Morse and the artist and theorist Warren Neidich took place over the course of two months in the fall/winter 2021–2022. The interview focuses on a body of work entitled the Hybrid Dialectics produced between 1997–2002 that served as bridge between his earlier performative reenactments and fictitious documents entitled, American History Reinvented, 1985–1993, and his more recent neon sculptures most notably the Pizzagate Neon, 2017–2021 and his A Proposition for an alt Parthenon Marbles Recoded: The Phantom as Other (2021–2022). Neidich’s project extends his interdisciplinary experiments carried out in the fields of cinema studies, structural film and apparatus theory which foregrounded cinematic devices and tools at the expense of the image. This forms the foundation of Neidich’s engagement with photographic medium as a form of politicized aesthetics embedded in a bidirectional embodied and extended cognition. His hybrid dialectics take off where artists like Michael Snow and Tony Conrad left off.” – Erik Morse

MONA presents Warren Neidich’s ‘Brain Without Organs’

MONA presents Warren Neidich’s ‘Brain Without Organs’

April 24, 2022 by Luke Netzley

“As an artist for more than 35 years, Neidich has looked to combine his background in neuroscience with a distinct creative flair to explore and question the evolving networks of control, surveillance and information prevalent around the world today and how they are redefining and reshaping systems of the brain.” — Luke Netzley

Galaxy Brain

Galaxy Brain

June 21, 2021 by Erik Morse

“Neuroaesthetics’ persistent fascination with a Kurzweilian “post-everything” future tense results in an ambitious project: Attempting to thread the interdisciplinary needle between the determinism of neuroscience and the subjectivism of aesthetics, it risks the rebuke of both disciplines. Moreover, it must maintain a vigilant campaign of reconnaissance and decryption at the vanguards of both art and science, all the while resisting the accelerating rhythms of capital that undergird both.” – Erik Morse

Warren Neidich on 'the Emancipatory Capacity of Art'

Warren Neidich on 'the Emancipatory Capacity of Art'

December 10, 2020 by Mark Segal

“I’m a wet conceptual artist because I want beauty and relevance to be a doorway to enter the work. I am also a 1970s Minimalist in many ways. I have tried to move their phenomenologically based work dependent on sensory experience to one that could be considered post-phenomenological and based on the conceptualizing brain. I engage with the past, but I’m trying to move the discussion in a different direction.” – Warren Neidich

How Can I Use Outdoor Spaces to Share My Art and Build Community?

How Can I Use Outdoor Spaces to Share My Art and Build Community?

December 4, 2020 by Anuradha Vikram

“While getting to know the east end of Long Island last spring, Neidich hatched a public art exhibition, “Drive-by-Art (Public Art in this Moment of Social Distancing),” which spawned a Los Angeles edition co-curated by Neidich, Renee Petropoulos, Michael Slenske and myself. This fall, Neidich has teamed up with curator Rita Gonzales (LACMA), poet Joseph Mosconi (Poetic Research Bureau) and writer Andrew Berardini to present “5-7-5,” a series of text installations by local and international artists on the marquee of the Theater at the Ace Hotel in downtown Los Angeles.” — Anuradha Vikram

Even with Museums Closed, Art Finds a Way Through Public Spaces

Even with Museums Closed, Art Finds a Way Through Public Spaces

November 10, 2020 by Jean Trinh

“Chief Curator Warren Neidich knew a theater marquee would be the perfect canvas for his text art project when he realized these venues weren’t being used during the pandemic. He contacted the Theatre at Ace Hotel and organized a curatorial team composed of Andrew Berardini, Rita Gonzalez and Joseph Mosconi. They brought together 10 artists for “5 – 7 – 5,” the name of which is a nod to the syllable structure of a haiku.” – Jean Trinh

The Neural Battlefield of Cognitive Capitalism

The Neural Battlefield of Cognitive Capitalism

November 6, 2020 by Anders Dunker

“The 2019 second edition of The Glossary of Cognitive Activism (For a Not So Distant Future) is a companion to the three-volume anthology Neidich co-edited entitled The Psychopathologies of Cognitive Capitalism (2013–’17), a highly collaborative project that emerged out of a series of conferences in Los Angeles, Berlin, and London. Drawing upon the wellspring of critical terminologies featured in those books, as well as in his own work, Neidich’s Glossary can be enjoyed as a stand-alone text: a timely reference for the perplexed, a navigational tool in the post-truth era, a roadmap for creative radicals, a strategic chart of a mental war zone, and a program of cultural healing. As Neidich’s installations of proliferating mind-maps amply illustrate, at the center of the artist’s work is the connecting, tracing, and modifying of networks on different levels. The Glossary seems to be intended, first and foremost, as an instrument for reclaiming one’s mental life at a time when it is being hijacked in ever more sophisticated ways. The Psychopathologies of Cognitive Capitalism canvassed a wide range of the resultant problems, from attention deficit disorder and insomnia to more opaque forms of maladjustment, alienation, and panic — all the consequence of a new wave of infiltration and colonization of the mind and brain.” – Anders Dunker

The Abyss of Uncertainty

The Abyss of Uncertainty

October 28, 2020 by James Salomon

“Warren and I knew each other from another era, and I’ve been watching (from a safe distance) what he’s been up to lately. His Drive-By-Art exhibition project was a stroke of genius and ingenuity because it came at a time when many artists felt hopeless and irrelevant under the circumstances (feelings not limited to artists – ahem – by the way). It was a shot in the arm, a morale booster. He then smartly took the concept to LA. I can go on about other interesting projects and noble acts he’s accomplished, but best to focus on the current, which is his curation of The Abyss of Uncertainty.“

— James Salomon

Ace Hotel in Downtown L.A. Launches Haiku Poetry Project on Its Marquee in Variety

Ace Hotel in Downtown L.A. Launches Haiku Poetry Project on Its Marquee

September 29, 2020 by Jem Aswad

“The project launched last week with artist David Horvitz (pictured above), and throughout the rest of the year Ace will host each artist’s work on the marquee that adorns the South Broadway side of the 1929 United Artists Theatre building. Those who are unable to visit the work in person will be able to view the work online, with additional online content to follow. […] “5-7-5” was created and programmed by a curatorial team consisting of Andrew Berardini, independent curator and contributing editor of Mousse Magazine; Rita Gonzalez, Department Head of Contemporary Art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Joseph Mosconi, co-director of the Poetic Research Bureau, and Warren Neidich, artist, independent curator and Director of the Saas-Fee Summer Institute of Art.” — Jem Aswad

Bring on the Night

Bring on the Night

September 2020 by James Salomon

“The Leiber Foundation Garden is a fantastic romantic reproduction of a simulated fantasy generated by an artificial reality based on infinite data points related to gardens making up its encrypted memory. It is not real even though we think it is and act as if it is so. We play at keeping the fantasy of its unreality unknown. One glitch however is unconcealed as an imperfect warped stump sitting alone with no time log in.” – Warren Neidich

Artists Are Essential Workers

Artists Are Essential Workers

September 23, 2020

“In his piece, Neidich utilizes the ready-made highway message board to shout out his provocative message to an artist community ravaged by the pandemic. Half of all museums and artist studios are on the brink of collapse. Can one say that artists are essential workers and art is an essential service especially at this moment of COVID-19?”

Artists Are Essential Workers

Artists Are Essential Workers

September 21, 2020

“In his piece, Neidich utilizes the ready-made highway message board to shout out his provocative message to an artist community ravaged by the pandemic. Half of all museums and artist studios are on the brink of collapse. Can one say that artists are essential workers and art is an essential service, especially at this moment of COVID-19?”

"Drive-By-Art (Public Art In This Moment of Social Distancing)", EE.UU.

"Drive-By-Art (Public Art In This Moment of Social Distancing)", EE.UU.

July 6, 2020

“Drive–By–Art offers a novel presentation and art viewing approach by taking advantage of the city’s pre-existing car culture and the intimacy and safety of the automobile. This public art experience is a call to action in a moment of economic, social, political, and spiritual catatonia, and an attempt to envision a different kind of cultural institution.”

The Pandemic Closed Art Galleries’ Doors. But Who Said a Gallery Needs Four Walls and a Ceiling?

The Pandemic Closed Art Galleries’ Doors. But Who Said a Gallery Needs Four Walls and a Ceiling?

June 11, 2022 by Anna Purna Kambhampaty

“Organized by Los Angeles–based conceptual artist and theorist Warren Neidich, ‘Drive-by-Art’ is a unique blend of the physical and digital that creates a socially distant art experience. Aimed at bringing art back to its starting place, the artist’s studio—where Neidich believes the work is in its purest and most powerful state—his shows allow spectators to use an online map to drive past works displayed on artists’ lawns, porches and mailboxes from the safety of their cars.”

— Anna Purna Kambhampaty

Signs are Everywhere

Signs are Everywhere

June 10, 2020 by Christina Catherine Martinez

“The drive to Venice from northeast LA took only twenty minutes—a rare thrill, edged with guilt. “This is where the elderly live, so you might not know that many of us,” architect Kulapat Yantrasast said, laughing, as I pulled up to his house for Kool Kat’s Kare Wash, a performance that offered attendees a free car wash (executed by assistants), a glass of white wine or Perrier, and an Ivy League–ish looking bumper sticker reading, “Proud Survivors: Homeschool University”—a cheeky nod to families with students homebound by Covid-19, though as a former homeschooler myself, I pasted it on my red 1997 Mazda Miata without irony. For being the go-to architect of such imposing LA art temples as the ICA, David Kordansky Gallery, and the now-shuttered Marciano Art Foundation, Yantrasast grokked the underlying pathos of such an encounter-hungry endeavor as Drive-By-Art. The performance was a low-key act of service that achieved the kind of causal connection rarely captured by the gravid connotations of cabalistic argot like relational aesthetics—but it was a sterling example of it.” — Christina Catherine Martinez

Pop-up outdoor art shows in LA fill a need for real-life art experiences

Pop-up outdoor art shows in LA fill a need for real-life art experiences

June 8, 2020 by Matthew Stromberg

“Over the course of two weekends in May, dozens of artists all over Los Angeles exhibited work outside their homes or in other public spaces for Drive-By-Art. The project was organised by the artist Warren Neidich, who saw the detrimental effect that the pandemic was having on the art community. “Artists depend on exhibitions, otherwise they’re isolated,” Neidich says. The West Coast edition was preceded by one in early May on the South Fork of Long Island in New York. Given the success of the East Coast version, Neidich enlisted the help of three Angeleno art-world figures—artist Renee Petropoulos, and curator/writers Michael Slenske and Anuradha Vikram—to help mount the project in LA.” — Matthew Stromberg

Exploring Los Angeles by Jeep, Asking "Is That Art?"

Exploring Los Angeles by Jeep, Asking "Is That Art?"

June 7, 2020 by Elana Scherr

“What started out as a reminder to stop and appreciate the art of the city around you became a reminder of the wider world that inspires art and changes cities.” — Elana Scherr

120 Artists Create a “Drive-by-Art” Exhibition Throughout Los Angeles

120 Artists Create a “Drive-by-Art” Exhibition Throughout Los Angeles

May 27, 2020 by Natalie Haddad

“Even at a time of social distancing and a marked decrease in LA’s legendary traffic, navigating through the expanse of LA’s vast East Side to locate the artworks (and finding parking at some sites, for those who want to venture out for a closer look at the art) can be a challenge, but the fun of Drive-By-Art lies partly in the discovery of artworks in unexpected places, and of exploring different areas.” — Natalie Haddad

Interview: Warren Neidich

Interview: Warren Neidich

May 16, 2020 by Brainard Carey

AUDIO: See direct link for audio interview.

VIDEO (left): Interview with Brainard Carey on Drive-By-Art (November 2020).

A Drive-By Art Show Turns Lawns and Garages Into Galleries

A Drive-By Art Show Turns Lawns and Garages Into Galleries

May 11, 2020 by Stacey Stowe

“No one was supposed to get too close to each other over the weekend during a drive-by exhibition of works by 52 artists on the South Fork of Long Island — a dose of culture amid the sterile isolation imposed by the pandemic. But some people couldn’t help themselves.

“At least this one looks like art,” said one man, as he stepped out of a convertible BMW onto the driveway of a rustic home in Sag Harbor on Saturday. He and two others examined the paintings, a cheeky homage to old masters by Darius Yektai that were affixed to two-by-fours nailed to trees. “Not like the other stuff.”

“The other stuff” was on display on the lawns, porches, driveways and garage doors at properties from Hampton Bays to Montauk, some from prominent artists and others by those lesser known. On a windy, blue-skied weekend, most people drove but others came on foot or by bicycle for the show, “Drive-By-Art (Public Art in This Moment of Social Distancing).”” — Stacey Stowe

Warren Neidich: Aktivistische Neuroästhetik als künstlerische Praxis in der Post-Wahrheitsgesellschaft

Warren Neidich: Aktivistische Neuroästhetik als künstlerische Praxis in der Post-Wahrheitsgesellschaft (Activist Neuroesthetics as Artistic Practice in the Post-Truth Society)

Bd. 267 - post-futuristisch. (Mai 2020) von Ann-Katrin Günzel

Vol. 267 - post-futuristic. (May 2020) by Ann-Katrin Günzel

“Im kognitiven Kapitalismus sind Gehirn und Geist die neuen Fabriken des 21. Jahrhunderts. Wir sind keine Fließbandarbeiter mehr, die Dinge herstellen, sondern mentale Arbeiter vor Bildschirmen, Kognitariate, mit der Welt an unseren Fingerspitzen, die Daten mit unseren Suchanfragen und Reaktionen in den sozialen Medien erstellen. Die Daten, die wir produzieren, werden nicht einfach zusammengestellt und analysiert, um unsere Einkaufstendenzen vorherzusagen, sondern aktiv verknüpft, um unsere Subjektivität zu gestalten, indem sie auf die Formbarkeit unseres Gehirns einwirken. Der Kognitive Kapitalismus ist aus dem italienischen Opera ismus und dem Post-Operaismus entstanden und ist in eine frühe und eine späte Phase unterteilt. Die frühe Phase ist von Prekarität, dem pausenlosen Arbeiten 24 / 7, der Verwertung, der Finanzialisierung von Kapital und Herdenverhalten, kommunikativem Kapitalismus und immaterieller oder performativer Arbeit geprägt. Die spätere Phase, in der wir uns heute befinden und die für mein Pizzagate Neon und das Video wichtig ist, subsumiert die frühere Phase, fügt aber eine zusätzliche Ebene hinzu. Der Fokus liegt nun auf dem materiellen Gehirn, insbesondere auf seinem neuronalen plastischen Potenzial, indem es die ihm innewohnende Wandelbarkeit normalisiert und dabei die neuronale Vielfalt in einer verschiedenartigen Population von Gehirnen und Köpfen homogenisiert.” – Warren Neidich

ENGLISH: “In cognitive capitalism the brain and the mind are the new factories of the 21st century. We are no longer proletariats physically working on assembly lines making things but cognitariats using mental labor in front of screens with the world at our fingertips creating data with our searches and reactions on social media. The data we produce is not simply collated and analyzed to predict our shopping tendencies but actively engaged in shaping our subjectivities through acting on our brains malleability. Cognitive Capitalism emerges from Italian Operaismo and Post-Operaismo and is divided into an early phase and late phase. The early phase is characterized by precarity, working 24/7, valorization, the financialization of capital and herd behavior, communicative capitalism and immaterial or performative labor. The later stage, in which we find ourselves today and which is important for my Pizzagate neon and video, subsumes its earlier phase but adds an additional layer. Its focus of power is now concentrated on the material brain, especially its neural plastic potential, normalizing its inherent variability and in the process homogenizing the neural diversity across a diverse population of brains and minds.” – Warren Neidich

Warren Neidich: Rumor To Delusion

Warren Neidich: Rumor To Delusion

Bd. 263 - Rebellion und Anpassung (Sep/Okt 2019) von Ann-Katrin Günzel

Vol. 263 - Rebellion and Adaptation (Sep/Oct 2019) by Ann-Katrin Günzel

“Der amerikanische post-Konzeptkünstler, Theoretiker und Neurowissenschaftler Warren Neidich (* 1958) beschäftigt sich in seiner künstlerischen Praxis analytisch und zugleich kritisch mit den Bedingungen der menschlichen Wahrnehmung. Dabei untersucht er, welchen Einfluss das Internet und neue Technologien, veränderte Kommunikationsmedien und -modalitäten sowie dadurch bedingt veränderte Rezeptionsmuster auf die materiellen Zustände des Gehirns haben. Die täglich aus aller Welt ununterbrochen, schnell und wiederholt als visuelle Zeichen simultan auf uns eintreffenden Meldungen und Berichte nehmen unser Bewußtsein direkt in Beschlag und lassen Relevanz, Tragweite und Substanz der einzelnen Meldungen dabei ebenso verschwimmen, wie deren Glaubwürdigkeit und Seriosität. Da unsere zeitgenössische Informations- und Kommunikationskultur vor allem das Visuelle betont, basiert auch unsere Wahrnehmung fast ausschließlich auf Bildern, was zur Folge hat, dass das Auge die menschliche Wahrnehmung in einer nie dagewesenen Weise dominiert. Aufgrund der veränderten Wahrnehmungsbedingungen verändern sich auch die psychischen und physischen Rezeptionsmechanismen der Menschen. Wenn das Gehirn in seiner Struktur einer permanenten Konditionierung unterliegt, die sich der Veränderung der Umwelt bzw. des Umfeldes anpasst, kann es, so Neidichs Analyse, über den „Prozess der umweltgesteuerten Neuromodulation“ gelenkt werden. Das bedeutet, dass manipulierte oder erfundene Nachrichten, sog. Fake News uns genauso ungefiltert als Wahrheit erreichen, wie wahrhaftige Fakten über das Weltgeschehen.” – Ann-Katrin Günzel

ENGLISH: “In his work, American post-conceptual artist, theorist, Warren Neidich (b. 1958), who studied neuroscience and medicine, analytically and critically examines the conditions of human perception. In doing so, he explores the impact the Internet and other new technologies, novel communication media and modes – as well as the new patterns of reception emerging from them – have on the material conditions of our brains. On a daily basis, newsflashes and reports from all over the world bombard us with information – continually, fast and ceaselessly. Taking the shape of visual signs, they flare up simultaneously, transfixing our conscious minds. Meanwhile, relevance, scope and substance of these pieces of information blur, and so does their credibility and reliability. Today’s culture of information and communication stresses the visual, stimulating us with an incessant flow of images. The eye is dominating human perception in ways it never has before. As Neidich reveals, the new perceptual conditions we live in also inform the underlying psychic and physical mechanisms of human perception. If the structure of our brains is being modelled and remodelled by the changing contexts and environments we inhabit, it also can – respectively – be conditioned by a “process of environmentally driven neuromodulations”, as Neidich warns. Thus, even manipulated and made-up pieces of information (so called ‘fake news’) affect us just as deeply and directly as truthful facts about actual world events.” – Ann-Katrin Günzel

A Day at the Beach and Some Other Interesting Times at the 2019 Venice Biennale

A Day at the Beach and Some Other Interesting Times at the 2019 Venice Biennale

August 12, 2019 by David Ebony

“In the Zuecca Project Space, “Rumor to Delusion” a show by Los Angeles- and Berlin-based artist Warren Neidich, addresses more recent political conundrums. The show’s centerpiece, an enormous chandelier with colorful neon signage, Pizzagate Neon (2017), explores the role of news organizations and social media in creating the present post-truth environment. Neidich uses as a starting point the odious “Pizzagate” rumor that coincided with Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign. Directly addressing Rugoff’s Biennale theme, “May You Live in Interesting Times,” Neidich considers this “rumor” as a seminal example of “fake news,” the present cultural malady of partisan disinformation. In tandem with Rugoff, he warns of its disturbing and far-reaching implications for the future.” – David Ebony

COGNITIVE CAPITALISM: Neidich, Denny, Popescu, Harney, and Ndikung at the SFSIA Berlin

COGNITIVE CAPITALISM: Neidich, Denny, Popescu, Harney, and Ndikung at the SFSIA Berlin

August 2, 2019 by Niklas Egberts

Niklas Egberts: Let’s start by talking about the central topic of the summer school. What constitutes capitalism’s becoming cognitive?

Warren Neidich: The mind and the brain are the new factories of the 21st century. We no longer work on assembly lines, producing things with our hands; instead, we work on various platforms on the Internet. There is a term for this new precarious class: it’s called the cognitariat. We are constantly producing data through searching and communicating online. That data, is crucially important to the way that feelings and emotions have become commoditized, all the while creating huge profits for the corporate elite.

The idea of cognitive capitalism is generated by the thought that the brain is not simply inside the skull but is also external to it, consisting of social, cultural, political and technological networks that are constantly evolving. These changing conditions in the world are recorded and activate changes in the mutable architecture of the brain – in a word, neuroplasticity.

Bellinis, sex and self-loathing: the diary of a party crasher at the Venice Biennale

Bellinis, sex and self-loathing: the diary of a party crasher at the Venice Biennale

June 17, 2019 by Christopher Taylor

“It’s my birthday. It’s not. It’s tomorrow, but I’m not going to let the opportunity to dine out on it pass me by. I drop in quickly at an installation to do with Carpenters workshop gallery at Ca’ D’Oro followed by an exquisite show at a popup of the legendary Colnaghi gallery. I also manage to take in a standout light installation by Warren Neidich at the Zuecca Project space Giudecca.” – Christopher Taylor

Historic Bauer Palladio Hotel Offers Prime Access To Venice's Newest Contemporary Art District

Historic Bauer Palladio Hotel Offers Prime Access To Venice's Newest Contemporary Art District

May 25, 2019 by Joanne Shurvell

“Giudecca Island, a ten minute ride across the grand canal by public vaporetto, has had a strong association with contemporary art for a while so it’s no surprise that it has just officially launched itself as Venice’s newest art district. The Venice Biennale Arte has used spaces on the island since the 1980s. And before that, in 1976, Giudecca was the site of various performances by Marina Abramović.” – Joanne Shurvell

Twelve Essential Offsite Exhibitions Of The 2019 Venice Biennale

Twelve Essential Offsite Exhibitions Of The 2019 Venice Biennale

May 19, 2019 by Joanne Shurvell

“Zuecca Projects on Guidecca island hosts American artist Warren Neidich’s solo exhibition Rumor to Delusion. The centerpiece of the show is a colorful neon display of words referencing the crazy “Pizzagate” fake news story of the 2016 Presidential campaign that accused Hillary Clinton and her staff of running a child sex slave ring out of the basement of the Comet Ping Pong pizza parlor in Washington D.C.” – Joanne Shurvell

FAD Magazine Venice Biennale Top 10

FAD Magazine Venice Biennale Top 10

May 17, 2019 by Lee Sharrock

“Warren Neidich’s punchy installation ‘Rumor to Delusion’ at Zuecca Project Space leaves a huge impression with its sensory overload of a 3 dimensional neon sculpture reflected in a giant mirror, juxtaposed by a multi-screen news channel spouting various forms of ‘fake news’. Inspired by the Pizzagate conspiracy and the contemporary post-truth era, Neidich presents a complex web of fabricated stories and hacked emails, which tell a dark story behind the rainbow-coloured sculpture. Curated by Lauri Firstenberg and Antonia Alampi, Neidich’s astute exhibition examines the Trump malaise of fake news through the bizarre Pizzagate myth, which was a fabricated story leading to a witch-hunt of American high fliers such as Hillary Clinton and legendary art world figures including Marina Abramovic.” – Lee Sharrock

‘I Didn’t Want My Art to Come Out While I Was an Actress’: At the Venice Biennale, Rose McGowan Reflects on Her New Life as an Artist

‘I Didn’t Want My Art to Come Out While I Was an Actress’: At the Venice Biennale, Rose McGowan Reflects on Her New Life as an Artist

May 14, 2019 by Sarah Cascone

On Cognitive Capitalism

On Cognitive Capitalism: An Interview with Warren Neidich by Hans Ulrich Obrist

Printed in 2000 copies on the occasion of the exhibition "Rumor to Delusion" by Warren Neidich, curated by Lauri Firstenberg and Antonia Alampi.

58th Venice Biennale, Zuecca project space, Venice. May 10 – July 31, 2019

Following the 2018 Berlin edition of Saas-Fee Summer Institute of Art (SFSIA), Hans Ulrich Obrist sat down with founder and director Warren Neidich to ask about cognitive capitalism, the overarching theme of the institute, and how it relates to his own expanded artistic practice. SFSIA is a nomadic, intensive summer academy (co-directed with Barry Schwabsky) with shifting programs in contemporary critical theory that stresses an interdisciplinary approach to the relationship between art and politics. SFSIA 2018 | Berlin, titled “Art and the Poetics of Praxis in Cognitive Capitalism,” built on the critical concerns of past programs—estrangement, individuation, and collectivity—in order to consider the performative power of poetry.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: As we are meeting in the context of the Saas-Fee Summer Institute of Art (SFSIA) which, as an artist and curator, you founded and have directed for the last four summers under the theme of ‘cognitive capitalism,’ I thought it would be interesting to start with the question: How would you define cognitive capitalism?

Warren S. Neidich: First of all, thank you for teaching this summer at SFSIA. I might start by mentioning that there’s already an excellent book on the subject by Yann Moulier-Boutang in which he lays the groundwork for understanding this term, and also, like yourself, Yann is a regularly returning faculty at SFSIA.1 In Cognitive Capitalism, Moulier-Boutang places the beginning of cognitive capitalism at around 1975 at a moment of profound crisis in the economy caused by the beginning of the cybernetic revolution. New technologies converged with social, political and cultural conditions to create new forms of accumulation and positive and negative externalities. Together these placed new pressures upon dead and living labor. A new form of non-linear, distributed machinic intelligence began to predominate and reconfigured the workplace and the workers’ role. Participatory workers were released from the assembly line and found themselves in front of a computer screen with access to a universe of knowledge at their fingertips.

Building on the earlier work of Romano Alquati, Raniero Panzieri, Mario Tronti and Tony Negri, a group of Italian political philosophers (Maurizio Lazzarato, Franco “Bifo” Berardi, Christian Marazzi, Silvia Federici and many others) began publishing in the journal Classe Operaia. They were early in predicting the effect on society brought about by these newly evolving forms of work. They understood the cybernetic future way ahead of anybody else and they realised that the new information age would change the way that people worked and lived, and they called this “cognitive capitalism.” Performance and immaterial labor became the predominant forms of labor in what would become known as “early cognitive capitalism.” Emotions, affects and feelings, once outside the scope and concern of capitalism, formed cognitive capitalism’s central core, and now were able to be capitalized. Immaterial labor became essential components of subject and subjectivity.

At that time, cognitive capitalism consisted of five or six components, and if you went to any of the biennials last year it was almost like every artist was taking a different theme from the annals of early cognitive capitalism, illustrating it in their own specific way. Ideas such as precarity, valorization, the financialization of capital, immaterial labor, communicative capitalism and real subsumption formed the conceptual frameworks they emphasized.

HUO: Some people may not be familiar with these terms. Could you briefly describe them?

WSN: Sure. The first element would be precarity. Labor became precarious and this began to pose a threat to stability of income and lifestyle. So “precarity” is a word that you hear all the time. Life has become unstable. In former times, in the days of our parents, there was the idea that a stable work environment and a secure job occurred within the time frame of set hours. One was a “company man” or “company woman.” In today’s flexible economy, one is now a freelancer or free agent, especially in ‘creative culture’ where everyone is an artist of one kind or another, and working from home is becoming increasingly normal. Precarity also suggests that everybody is teleworking alone and isolated from direct contact with others. Instead they are working and waiting by their computers, or iPhones, awaiting the next tweet, Facebook post, or email informing them of their next job opportunity. Which, by the way, might mean “prosuming” with other designers online, chatting with other members of a think tank, or even searching data, which creates data that is later bought and sold. As a consequence there’s this kind of edginess, an unease, that we experience as we are linked by our iPhones as nodes in an immense communicative network which is also creating a lot of anxiety. This is the idea of precarity.

HUO: Precarity also means the end of all safety nets in a way – so people are worried.

WSN: Yes, people are worried and in a state of unease that permeates society as a whole. Also, there’s another definition of precarity that concerns a kind of struggle taking place in consciousness itself. That ‘real’ memory, the directly experienced memory of objects and activities performed in the material world, is being subsumed by virtual memory. In other words, the memories that we are engaged with in the virtuality of the simulacrum, as Baudrillard put it back in the 1980s, where the simulated world becomes the dominant context within which we experience the world and digital objects and relations from that world outcompete their real world counterparts for the synaptic spaces that constitute the neural architecture of the connectome, the elaborate matrix of neural connections of the brain. These simulated images are mechanically engineered images of attention, what Paul Virilio called ‘phatic images’, in other words more emphatic images. Accordingly, borrowing from the ideas of Gerald Edelman and Jean-Pierre Changeux, they act as powerful neural-plastic modulators and they outcompete so-called ‘real world’ relations. If, in fact, we can even consider anything real, for the brain’s neural space.

We’re spending more and more of our waking time on the internet and, as a result, a greater and greater proportion of our conscious time is being spent interacting with the constructed and engineered sensory data of the net. Now the images and sensations we experience are modified further by software agents creating image bubbles based on our past searches which, as a result, seem closer and more familiar. These images capture our attention more intensely. Attention has been shown to be very important for the production of memories. As a consequence our memories, the images we remember, are a kind of combination now. They’re a collage of both ‘real’ and ‘virtual’ memories and, to a certain extent, the virtual memories are more powerful. This is what I wrote in my book Blow Up: Photography, Cinema and the Brain back in 2003. I understood the crisis of the main character Thomas, at the end of the movie Blow Up, as a confusion occurring between these two forms of memory reconstituted in the mind’s eye (or working memory) and what Gilles Deleuze called the image of thought. As I explained, Thomas’ memory was precarious in that he could no longer determine the location and source of the memories he retrieved. He could no longer tell which memories were from the archive of his own photographic practice, especially those from the pictures he made of an affair between two lovers in a park which he enlarges (blows up) in the dark room and those generated from his own memories from his personal experiences and relations with the real and natural world, so-called ‘real’ memories. The fictive tennis match he plays and performs at the end of the movie represents a crisis of precarious memory and, as such, a form of induced schizophrenia. That is what creates the crisis of precarity.

The second aspect of cognitive capitalism is referred to as “24/7” and, of course, Jonathan Crary’s book 24/7 is a great resource for further reading. Whereas previously we had a workplace we went to everyday from 9 to 5 (whether it was a bureau or a factory) and then we would go home and enjoy our leisure time, today everything is work. We never stop working. As opposed to the previous model, which Marx called “formal subsumption,” this he called “real subsumption.” Everything that we do now is work. We go to a party and check our emails and see a friend’s Facebook post and we ‘like’ it or we don’t, and we post an image of the party on Instagram. We are constantly working. Our Facebook likes and Instagram posts are data that become part of the “big data” network, and this data helps to produce a singular data profile that is then used by corporations to invite us to like and dislike certain of their products. We are constantly working and we are working for free. We have made a Faustian pact, a kind of agreement with these companies – with Facebook, which gives us a lot of joy and pleasure, or Google, which makes us smarter because it gives us access to a shared, cooperative encyclopedia of knowledge at our fingertips. We have made that contract and so 24/7 is the second component of cognitive capitalism. In my upcoming book, The Glossary of Cognitive Activism, I have coined the term ‘neuro-subsumption’ and stress that in the future, as our brains are hooked up to the internet, there is a possibility that even our unconscious, and non-conscious (or implicit neural activity), will be monitored and coded. This will mean that every one of our thoughts will be transformed into data and end up circulating in the cloud.

The third component of cognitive capitalism is what is called the ‘valorisation economy,’ which is related both to precarity and these other things that we have been talking about because the valorisation economy substitutes valorisation for value. Value is still around, but it is subsumed. Through interventions in the social mind by advertising, public relations, rumor and fake news, a commodity gains added value. Corporations (and governments) are no longer selling the object – the car, or the material. They are selling the experience of the car. Imagine a commercial in which two beautiful people are driving down Highway 1 along the Pacific Coast of California, wind blowing in the woman’s hair. This incredible experience is communicated to the viewer like a movie. That’s all part of valorisation. A Nike shoe, which costs $17 to make in the Philippines, becomes £117 on the high street. This increase in value is added by its capacity to be valorized by the social hive mind – the importance of having celebrity basketball players wearing the shoe is an essential component of this story. This is the key to cognitive capitalism. The production of the object, of this shoe for instance, doesn’t end when it comes off the assembly line, but is constituted in the social mind and in the neural networks of the brain. This is the new form of work, or mental labor, in cognitive capitalism. The work is unpaid, but actually generates added value for the corporation selling the object. It is important to note that when I talk about the ‘brain,’ I’m not only talking about the thing inside your skull. I’m talking about the situated body as well, and I’m talking about everything in our world that we interact with. Neural plasticity and cultural plasticity are con-substantiated and evolve together. The sociological and semiotic conditions of the cultural milieu are all extended and externalized capacities of the brain, and one can say that if these capacities were intracranial instead of extracranial we would call them cognitive.

HUO: How does cognitive capitalism enter your artwork? How does it enter the practice of art in general? I was looking at your book, The Color of Politics, yesterday and it’s a kind of A-to-Z, an alphabet of your different neon works which connect internet phenomena and society. Some of them are platforms, like 4chan, while others are names of people, or protagonists, like Barack Obama. Others are basically neologisms. Can you talk a little bit about this?

WSN: To answer, I would like to continue this discussion about cognitive capitalism because my artwork is the contribution I have made to understanding it. First of all, I don’t consider writing, organizing and theorizing as separate from my art practice. As Deleuze stated, artworks create new sensations and my artwork takes its point of departure from that seminal idea. I understand my work in the context of what I refer to as a ‘wet’ conceptualism, as opposed to a ‘dry’ conceptualism. In ‘dry’ conceptual practices, such as the early work of Joseph Kosuth, the immaterial works of Robert Barry, or the works of Sol Lewitt, beauty is drained from the work of art in order to make it as purely disinterested and as cognitive as possible – to remove its capacity for emotion that played such an important role in Kant’s analysis of beauty in his “Critique of Aesthetic Judgement.” According to the ‘dry’ conceptualist position, beauty and emotion muddle the interpretation and experience of the concept of the work. Sol Lewitt famously stated that the idea is the most important aspect of the work, that all planning and decisions should be made beforehand, and execution is a perfunctory affair.

In ‘wet’ conceptualism, beauty is not considered a hindrance to the reception of the work of art as a theoretically-driven conceptual and cognitive construct. It is a door through which the visitor can enter the work. In fact, it accentuates it. All decisions are not made beforehand and production is an important part of the process of creation, including decisions made mid-stream. However, ‘wet’ conceptualism is also not concerned with essences or universality, but rather its singular capacity to be understood and appreciated by the multitude. However, ‘wet’ conceptualism is pertinent to our times in relation to cognitive capitalism because instead of being directed to the senses and perceptions, it is directed to the organic, living apparatuses of the neural-plastic brain. It has the capacity to transform and emancipate the cognitariat’s thought processes in the mind’s eye. In late-stage cognitive capitalism, ‘wet’ conceptual art produces changes in the intracranial and extracranial brain – redefinition put to work.

HUO: How so? Is this what you have meant by “activist neuroaesthetics”?

WSN: In 1996, I co-founded (with Nathalie Angles) the website www.artbrain.org and the The Journal of Neuroaesthetics in which I put forth the notion of an activist neuroaesthetics. Rather than a positivist, or empirical, neural aesthetics promoted by neuroscience which attempts to subsume artistic processes of creativity and exploration and substitute it with a scientific one, the activist understands that art has the capacity to deterritorialize neuroscience and challenges its authority as the only proper research methodology pertaining to the distribution of the sensible. It understands positivist neuroaesthetics as a tool of imperial neoliberal global capitalism in creating the perfect cognitive global consumer, or the perfect cognitariat, whose neural architecture is optimally molded for the quick and attuned work of the net. Artists, on the other hand, do the opposite by looking for opportunities to undermine this optimization, as well as by creating other neural logics that aspire to alternative forms of consciousness. Artistic labor is now concerned with mutating the conditions of the cultural habitus, or the extracranial brain, with concomitant effects upon the material intracranial brain. Finally, activist neuroaesthetics assumes that if we have the will and foresight, this could become a political call to arms. It suggests the possibility that brain sculpting might be an important tool for social and political transformation.

HUO: How does this relate to your teaching? Is it all part of one practice?

WSN: My work as an artist is not just about making art. Obviously it’s also about pedagogy and it’s also about writing. It’s surprising how many people don’t know about cognitive capitalism and so, in a way, one of my roles is as consciousness-raiser. In 2005, I started coming across the writings of Franco “Bifo” Berardi, Christian Marazzi, Maurizio Lazzarato and Toni Negri – authors concerned what was called “post-workerism” (which followed workerism in Italian literature). I realized that it could become a powerful instrument in understanding what I was trying to talk about in neuroaesthetics. I started getting involved in this discussion first by inviting Maurizio Lazzarato, Yann Moulier-Boutang and Paolo Virno to my conference at the Delft School of Design, “Trans-thinking the City,” followed by the book I co-authored with Deborah Hauptmann, Cognitive Architecture: From Biopolitics to Noo-politics. At that time, I was doing a doctoral program in Architectural Theory with Dr. Arie Graafland. I collapsed the idea of multi- and interdisciplinarity into the idea of trans-thinking, in which ‘inter’ and ‘multi’ became frames of mind and thought. These practices were interiorized as apparatuses emancipating forms of thinking. In other words, they had actually become part of the implementation of the way that we think. I realized that many of these authors were referring to the brain and cognition in a very general and metaphorical way. There was a specificity missing that I thought I could contribute as a way of broadening my own theoretical and discursive base which had began in the book Blow-up: Photography, Cinema and the Brain as well as modestly rendering their arguments even more important. They didn’t have a certain kind of knowledge that I had about neuroscience. Importantly, my knowledge was not akin to positivist and reductionist thinkers, but more attuned to the work of Francisco Varela which was anti-reductionist and emphasized the power of emergence. That is how my interest in bringing these themes together arose and led to the three volume work, The Psychopathologies of Cognitive Capitalism, and the [soon-to-be-released] Glossary of Cognitive Activism (For a Not so Distant Future). The Color of Politics contains an early rendition of the glossary linked to the words used to make the sculpture and is in fact the catalogue for the exhibition I made at the Kunstverein am Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz. It is a model for understanding the political crisis we are all involved in, and tries to define what that is and possibly offer some solutions.

HUO: I remember seeing pictures of your neon sculpture “The Statisticon Neon” that you made in Berlin. Could you explain this further?

WSN: The Color of Politics describes two works in neon that I presented at the Kunstverein am Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz. Downstairs in the lobby was the “Statisticon Neon”, and upstairs were three works that together connected the political conditions of McCarthyism to our moment of right wing populism today. “The Statisticon Neon” was in many ways a homage to Joseph Beuys’ work, “Das Kapital Raum 1970-1977”, which was originally shown in the German Pavilion in Venice in 1980, and today is on loan to Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie, the collection of which is partly on view at the Hamburger Bahnhof. I displayed my work on a collection of blackboards which echoed Beuys’ installation at the museum, where they are filled with handwritten cursive notes about art and capital. At the time of this work, the immanence of the information economy was so real as to be a source of inspiration for Beuys despite the fact that there was no public internet, social media platforms or big data. I superimposed my neon sculpture – which commented on many of the issues he was interested in, but did not live to see – over those blackboards, much like a technicolor film in contrast to Beuys’ work in black and white. Key to the work was the central position of the term “Statisticon” which refers to the future condition of extreme data in which the brain and mind are directly linked to, and controlled by, the Internet of Everything. As such, it points to the future of a surveillance economy.

The upper galleries showed how post-truth society and fake news (characterised by the conspiracy theory known as Pizzagate) were linked to McCarthyism. I had already begun to work on this question in Los Angeles in “Book Exchange: The Hollywood Blacklist” exhibited at the Printed Matter L.A. Book Fair in 2015, and, later, in my exhibition, The Palinopsic Field at LACE in 2016. Crucial to this story were my two works, “The Archive of False Accusations”, and “Double Jeopardy: The Afterimage Paintings”. In the “Archive of False Accusations”, press clippings reporting on what was known as the “Lavender Scare” were presented in four lavender neon-lit plexiglass vitrines. One of those vitrines exhibited press clippings relating to Donald Trump and Roy Cohn, an American lawyer best known for his role as chief council to Joseph McCarthy, who was also a mentor to Donald Trump. This vitrine plays an important role in relation to the second work, “Double Jeopardy: The Afterimage Paintings”, which consists of three neon sculptures which spell out the names of the German emigrants Bertolt Brecht, Hanns Eisler and Lion Feuchtwanger, all of whom were later blacklisted in Hollywood as communists and, as such, were never granted a star on Hollywood Boulevard. The names were interspersed with four realistic paintings of stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. The paintings are empty stars except for the logo, signifying the different star categories such as live theater, motion pictures, radio or television. Spectators stare at the blinking red neon for 10 seconds, after which time they redirect their gaze to stare at the center of the star in the painting where the afterimage of the artist’s name appears. Thus, each participant rewrites the past and rectifies the injustices done to these artists by projecting their names, if only for seconds, on the adjacent star painting. Their actions modify history as it is known, and point to the power of the people to alter a mutable and becoming history.

HUO: How does Pizzagate fit in? Comet Ping Pong is a pizza parlour owned by James Alefantis, the former boyfriend of David Brock, and was basically the venue for this alleged conspiracy, but can you elaborate on your interest?

WSN: Pizzagate is a now debunked, one might even say preposterous, conspiracy theory that went viral towards the end of the 2016 presidential election. It was an event – a fictitious event, one might even say a rumor – disseminated on newsfeeds, chat threads and message boards including 4chan and Reddit, as well as Twitter. The theory proposed that Hillary Clinton and the people in her campaign were operating an international sex-trafficking ring out of the Comet Ping Pong pizza parlour in Washington D.C. The so-called proof of which resulted from the hacking of Hillary Clinton’s campaign manager’s (John Podesta) personal emails.

HUO: Which is no different than what Edgar Morin already understood some years back. Edgar Morin, now in his nineties, is a French philosopher acquaintance of mine who wrote La Rumeur d’Orléans, concerning the rumor that in a women’s wear shop in Orleans the customers would actually disappear. They would go to the shop, try on a dress in the fitting room, and then disappear never to be seen again. This was actually a right-wing anti-semitic rumor in Orleans at the time targeted at the owners of this shop. As a consequence, their business was completely destroyed. It’s the precursor to Pizzagate.

WSN: Yes, propaganda and fake news have been around some time, but the Internet is provoking a much stronger reaction – and the rumor is related to the emergence of bottom-up, socially constructed truths.

HUO: Very sadly, with the current rise of antisemitism in France, it’s again also of great relevance in that regard, as Umberto Eco pointed out to me in my last conversation with him, but it’s interesting, in a way, that the Rumor of Orleans and Pizzagate are connected.

WSN: You are right. Rumor has taken on greater importance in cognitive capitalism and is related to what is referred to as valorisation and valorized economies. We live in this valorised world, and it’s very important. Truth is more about a story or a narrative that constitutes an arrangement of objects, things and the networks they create. Truth becomes an attribute of how viral the story is and how much attention it can attract. Truth is conditional on the distribution of data in the cloud. The “Pizzagate” sculpture is an attempt to talk about the network relations that are important in the production of these fake news stories.

Fake news is related to propaganda but in many ways it is different. Propaganda is a top-down phenomenon in which a sovereign agent constructs stories to engage the populace in a particular believable way with the aim to change their actions. Fake news is a bottom-up phenomenon which is the result of a welling up of stories concocted on real and fake social media pages which have begun to be believed. Their sheer massive distribution, as well as their emergent qualities, make them powerful modulators of public opinion. They colonize the attention of the populace by providing engaging content. The attention economy, and its economic capacity, is directly related to how many eyeballs it can induce to look at its content. The “Pizzagate Neon” takes this argument one step further as it talks about the power of these fake news stories to sculpt the neural plasticity of the brain through a neural-synaptic process. In the attention economy, where because in this surfeit of images and information that we’re exposed to it’s impossible to pay attention to everything, attention itself becomes a commodity. It becomes important for corporations and advertisers to capture our attention through various strategies like sensationalism, special graphics and editing techniques that make the information they want to convey more salient. “Clickbait”, which appears in the sculpture, is analogous to baiting a hook to catch a fish. You make the bait as attractive as you possibly can. Clickbait is similar, but it turns out that fake news is a much more powerful attractor and stimulator of attention than real news to instigate cognitariat clicking. Clickbait is also a powerful sculptor of memory. In her essay, “Attention, Economy and the Brain”, Tiziana Terranova speaks directly to this question, highlighting the impact of Internet usage on the cognitive architecture of a neuroplastic and mimetic social brain. My point is that all these different alt-right memes, different kinds of platforms, Kek, all of these different mechanisms of the new far right are the new apparatuses at play engaged in the attention economy and are actually changing the neural plasticity of the brain and forming new kinds of memories. That’s what this sculpture is about.

HUO: Of course, the actual story of Pizzagate is also part of the work. Edgar Welch, for example, entered the pizzeria with a gun believing the truth of that rumor. He, as well as the other protagonists, make an appearance in the work along with the internet wide phenomena, but also the art world enters the story. I was interested in seeing Louise Bourgeois’ name. I didn’t remember the connection between Louise Bourgeois and Pizzagate. Can you elaborate?

WSN: Thank you for bringing this up because one of the most important aspects of the sculpture and video I made called “Pizzagate: From Rumor to Delusion” is the story of how various artists and their work became of interest to the alt-right as examples to back up their fake news story, as well as, to impress on their base the lascivious nature of the Democratic candidates – as if the artworks were a valid reason for scorn. This story involved the art collection of Tony Podesta, the brother of John and a friend of James Alefantis, the guy who owns Comet Ping Pong. The work that he has in his collection is very sexually explicit, very edgy, and some of the work owned by Tony Podesta was hanging in Comet Ping Pong, especially the work of Arrington de Dionyso. John Podesta, as you know, was the campaign manager for Hillary Clinton, so when they hacked John Podesta’s emails, and when this whole phenomenon of the Pizzagate rumor started, the reporters went to Comet Ping Pong where they coincidentally came upon what appeared to them as “weird” art – so here [in Bourgeois’ work] we have this story of childhood molestation and this very sexually explicit ‘weird’ art on the walls. This confluence created a story that went viral, and, all of a sudden, this rumor starts becoming “true” and believed. What also happened is that on alt-right news feeds there were all these stories about Tony Podesta and his weird art collection, and then, of course, the Marina Abramovic part of the story emerges out of this context. “Spirit Cooking”, a performance at Marina’s loft in New York City to thank her donors, mutated into a story concerning witchcraft. Of course, witchcraft is part of a larger feminist discourse and it is quite normal in the art world to discuss and represent such a story, but to the alt-right base it is blasphemy.

HUO: You must absolutely talk to Edgar Morin because Rumor of Orleans, a book from the early 70s, is uncanny in the similarities.

WSN: Thank you for letting me know. I will certainly get a copy.

HUO: So, what’s next? What’s happening in the studio right now?

WSN: Well, in the studio right now is a work about neurotic AI and I’m continuing my work from 2004 on the phantom limb syndrome. First, I’m creating phantom limb boxes that are based on devices that help to cure phantom limb pain. Sometimes, for example, when people have their arm amputated they develop pain, and there’s a kind of box called “the phantom limb box”, invented by the famous neuroscientist V.S. Ramachandran which is a mirror box that helps cure it. What I’ve been making are Donald Judd-type minimalist sculptures that stand in as phantom limb boxes. In the gallery, I bring in amputees who actually have phantom limb pain and use the artwork to cure them. That’s one thing that I’ve been working on. It’s all about the eternal return.

HUO: That’s a more Nietzschean trope.

WSN: Yes, but at the same time I’m doing a lot of work on artificial neural networks, and it’s very complicated as to why I’m doing that. I’ve been going to old neon stores and it turns out they have been changing all of their signs from neon to LED. One kind of technology is being supplanted by another, a kind of extinction of neon. Neon is being extinguished, so I’ve been going in and collecting these old neons and making artworks based on artificial neural networks. The found neon in each piece is creating what I call the “poetic artificial neural network”, so it’s not about optimization, it’s about thinking about a future AI, and trying to think of ways that this AI could be based on the poetic. Artificial neural networks are structured in specific ways. You have the input and you have the output, but you also have what is called the “intermediary zone” and the intermediary zone was originally based on the structure of the retina. Basically, early neural networks and artificial neural networks are based on real neurological and neurophysiological structures. They used the retina of the eye, for vision, as one of the early structures to simulate. In the retina you have the rods and the cones, which take in the light and transform the light into energy, and then you have a series of intermediary zones which are bipolar cells and amacrine cells and horizontal cells, and then finally you have the output to the brain through the ganglion cells. Those three layers are the layers of neural networks, and when you have more than one layer in the intermediated zone changing this energy into a form that is information, then you have what is called Deep Mind. This provides the basis for these new assemblages that I have been making from found neons. All the neons contain a sausage, or, if you like, the smile of an emoji, and each is based on a version of the sexed body, and in this way they are a contemporary rendition of Marcel Duchamp’s “The Large Glass.” Importantly, the intermediary zone, in which the incoming information is being transformed into the output, is based on assemblages of different histories because the found neons used vary in age. Some are over 30-years-old, some are 20-years-old, some are 1-year-old. One was part of a sign for a sex shop and another was a sign for a food store, yet another came from an art project that an artist never picked up, so there are all these different kinds of stories that each one of the neons embodies that are contained in the neural network. Together they become a kind of poetic information system.

One of the other things that I am working on is a lecture called “2050: For What Will We Use Our Brains?” In this lecture I intend to map the effects of contemporary technology on the brain. Like the revolution that described the last half of the previous century, we to are faced with a technological acceleration which is putting pressure on what subjectivity can be. I am speaking about the neural-based economy which maps out the late stage of cognitive capitalism. First, the material brain, its structure and function, has become the model or template for the production of the new technologies we have already mentioned like pattern recognition, AI, artificial neural networks, brain computer interfaces and cortical implants. Secondly, the impetus for these new technologies is to outsource the functions of the intracranial brain to an assemblage of externalized apparatuses that constitute an extracranial brain which has the ability to substitute for and surpass the human laborer. We already use GPS to find our way and recent research from Veronique Bohbot at McGill University, has suggested that constant use in older people may have damaging effects to the hippocampus. Just on the horizon are forms of artificial intelligence that will replace doctors, lawyers and accountants. The things that the human brain used to do, technology and machine-to-machine learning will do on our behalf and will do more effectively. The question is, what will we use our brains for? I’ve constructed a theory based on “the neuronal recycling hypothesis” of Stanislas Dehaene, who works in the Pasteur Institute in Paris. It posits that cultural inventions evolutionarily invade older brain circuits. In this case, it argues that the inferior temporal area of the temporal lobe of macaques share attributes with the human visual word-forming area, and that the invention of writing (after it became widely used), colonized that area of the brain and transformed it into its new use. I am arguing that the widespread use of telepathic technology will also put pressure on areas of the brain that maintain prerequisite structures that can be easily modified. At first, it will be technologically enhanced, but gradually it will become naturalized.

HUO: Research into mental images gets us pretty close to telepathy. I mean, if I can think of an image then we don’t need to go through a photograph anymore – you actually see that image, we have a telepathic relationship, a telepathic connection.

WSN: Right, but there are two important elements. At first, brain-computer interfaces required the electrode to be implanted in the brain which facilitated, after training, a paralyzed person’s ability to use his or her brainwaves to move a cursor on a computer screen, to control a robotic arm for feeding, or to control the movement of a wheelchair. Then, the technology advanced so that this type of control could be accomplished by projecting brain waves through a wireless Emotiv headset. Recently, the use of brain-computer interfaces has expanded. For instance, Neurable’s BCI headset for HTC Vive is being used for interfacing with virtual reality and playing competitive video games against another person wearing a similar device, as in the game Brain Arena, but it does not stop there. Linking up brain-computer interfaces to the Internet-of-things is already being experimented with such as with the brain-computer interface-based Smart Living Environmental Auto-Adjustment Control System. Gradually, if we believe Moore’s Law that computer processing capacity doubles exponentially each year, then we begin to understand that more and more of our technologies will become linked through brain-computer interfaces forming a system of integrated technologically enabled telepathic capacities. Just as we saw for writing, gradually there will occur a form of accumulation that I speculate could have neuromodulating capacity.

Returning to the neuronal recycling hypothesis, Dehaene states that writing and reading are only 5000 years old, its formal beginnings started with the invention of Sumerian writing tablets. However, molecular geneticists arguing in another context hypothesize that the changes necessary for the establishment of a reading module in the brain would take one million years. Placing a patient, or volunteer, inside of an MRI machine and having them read or write can provoke an area called the fusiform gyrus, so Dehaene asks: how is it possible that in 5000 years a material change in the brain such as this could take place? His response is his neuronal recycling hypothesis. Novel capacities like reading and writing may be acquired as long as they can find a suitable area in the brain to accommodate it, perhaps maybe even colonize it. The novel cultural function must locate an area whose function is similar and plastic enough to accommodate it. What I would like to suggest is that there must be suitable pressure provoked by an accumulation of cultural artifacts operating in the cultural milieu to select out from the population individuals who have a predisposition to reading signs. In any population there are a variety of individuals who have unusual capabilities. Some men and women have greater capacity to hit a tennis ball, for example. There is also an inherent variability in the processing of symbolic information in the area of the occipito-temporal gyrus or fusiform gyrus inherited from our simian forefathers. He argues that the area used by macaques, a type of monkey, to understand another primate’s facial expressions is appropriated in humans for reading and, if you compare the brain scans of people reading to the facial recognition area in primates, the areas that light up are indeed located very close to each other. What I am hypothesizing is that in the future, as telepathic technologies become more and more prevalent, there will come a time when their accumulated presence induces changes in the brain. Those changes may be gradual and linked to comparable changes in the cultural milieu induced by embedded technologies in the built environment or in virtual reality. As the brain is both intracranial matter as well as outsourced, extracranial tools and devices, the process will be a co-evolutionary one. Like with reading and writing, there will come a tipping point in which telepathy will colonize an area of the brain with the right number of innate capacities and induce it to record and process telepathic information without technological software and hardware – or just transform it, as we may already have telepathic capacity, as you said. These telepathic capacities will be engaged with and be made more powerful.

HUO: Which, of course, will make Rupert Sheldrake more relevant again.

WSN: {laughs} That would be something.

Hans Ulrich Obrist (b. 1968, Zurich, Switzerland) is Artistic Director of the Serpentine Galleries in London, and Senior Artistic Advisor of The Shed in New York. Prior to this, he was the Curator of the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. Since his first show World Soup (The Kitchen Show) in 1991, he has curated more than 300 shows.

Show Me Your Selfie, Aram Art Gallery, Seoul, Korea

Show Me Your Selfie

Aram Art Gallery, Seoul, Korea

Exhibition 7/17-10/6

'This Is Not a Selfie’ tackles the interesting history of self-portraits

'This Is Not a Selfie' tackles the interesting history of self-portraits

September 10, 2018 by Joanne Milani, Times Correspondent

“Warren Neidich has carried on his own guerilla war with history in his 1993 “Unknown Artist” series. He added his own face to group photos of famous artists of the past. As the “unknown artist,” he appears next to a young Salvador Dalí in one group photograph. He is next to a leather-jacketed Andy Warhol in another. By doctoring the original photos, he declared “an assault on a truly verifiable record,” i.e. the documentary photograph.

Neidich wasn’t the first artist to have fun with doctored identities. In 1927, T. Lux Feininger did a poetic take on stolen identity when he disguised himself as Charlie Chaplin, complete with mustache. You can see “The Little Tramp” in Feininger’s photograph. It’s a hazy face glancing at you through the frame of a picture or mirror. That’s Feininger’s way of telling you that this image is a fantasy.” – Joanne Milani

Böser Blick in unser Hirn (A dirty look into our brains)

A dirty look into our brains

Profound art by Warren Neidich at Priska Pasquer Gallery

They call it a ‘Trump Cup’. It’s a coffee mug, the rim of which we’re invited to touch. Like any other mug, it is perfectly circular. However, if look at it from where we stand (that is, through a glass panel installed above the object), the mug’s rim appears to be oval. Which are we to trust, thus, our hand or our eyes? With the object described above, Warren Neidich finds a pithy allegory for the today’s phenomenon of ‘fake news’.

On view at Priska Pasquer gallery there is yet another composition which elaborates on the same problem more explicitly. “Pizzagate” is the title of a spherical accumulation of words and arrows crafted in colourful neon tubes. This could be a representation of the brain, just as well as it could be a materialization of a digital cloud.

“Pizzagate” refers to a smear campaign, which damaged Hillary Clinton’s image decisively during the 2016 US presidential campaign. Trump’s campaign team claimed that a paedophile ring operated out the basement of a pizza parlour in which Clinton liked to dine. Agitated by the news, an armed man finally broke into the restaurant and started shooting around wildly. As it turned out, though, there weren’t any paedophiles, nor did the pizza parlour have a basement.

Warren Neidich, professor at art academies in the US and in Berlin, is a trained neurologist and advocates a theory, according to which fake news enter into and leave traces in our brains – even if we know them to be absurd and made up. Neidich’s latest exhibition in Cologne is titled “Neuromacht”.

The artist believes our thoughts to have the power to change – that is, if we are ready to explore terrains outside our habitual streams of consciousness, which is where our potentials for creativity reside. To connect information in unexpected ways means to think against the grain of dominant consumption oriented thought patterns.

The 60-year-old artist provides concrete examples in his work “Noise and the Possibility of a Future”, which is also the subtitle of his show. He smashes loud speakers, puts their pieces back together, and accompanies his newly collaged sculptures with the soundscapes of their destruction. In this way, he liberates the object from its common use and allows it to become something new.

And there is a good sense of humour, too, in each and every one of Neidich’s installations. The artist’s “Wrong Rainbow Paintings” are colour circles, the black centres of which resemble the iris of a human eye. The artist has also taken an interest in the rainbows depicted in historical landscape paintings – their colour scales being oddly unrealistic. As we watch Warren Neidich extract the colours of a Caspar David Friedrich rainbow, we may ask ourselves why the ‘wrong’ representation manages to capture our emotional truth much more accurately than any cold realism ever could. Prices between 25.000 and 120.000 Euro.

Translation: Katharina Weinstock

How noise and neons give birth to new worldviews

Mit Noise und Neon zur neuen Weltsicht

(How noise and neons give birth to new worldviews)

July 24, 2018 by Nelly Gawellek

How noise and neons give birth to new worldviews

Warren Neidich’s introduction into ‘Neuro-Aesthetics’ at Priska Pasquer